L-R: Subhakanta Bal, MD, Naina Lal Kidwai, senior advisor., Chandresh Ruparel, MD & India head, Aalok Shah, MD and co-head India, Rothschild & Co.

L-R: Subhakanta Bal, MD, Naina Lal Kidwai, senior advisor., Chandresh Ruparel, MD & India head, Aalok Shah, MD and co-head India, Rothschild & Co.

Image: Apoorva Salkade for Forbes India

The rise of Indian entrepreneurship has been accompanied by a concomitant increase in deal making and fundraising. Nowhere is this trend clearer than in the mid-market segment where companies are on the lookout for Rs500-2,500 crore deals.

Take the case of Bengaluru based agro-chemical company Cropnosys. In December 2023, it was in the market for raising funds. Its businesses that straddled herbicides and fungicides to insecticides and micronutrients, had seen rapid growth with revenues at Rs672 crores in FY23. Profitability and margins were healthy at Rs109 crore, or 20.9 percent.

While it had managed to double capacity in 2022 through internal accruals, it now needed to scale rapidly and reduce its dependence on imports for manufacturing key agri chemicals. Its new plan: A fivefold increase in capacity at its Vapi facility.

Enter Rothschild & Co, which had till then done two deals in the agro chemcials space. While the banker was confident it could sell the story to investors, the size of the fund rise surprised many in the industry.

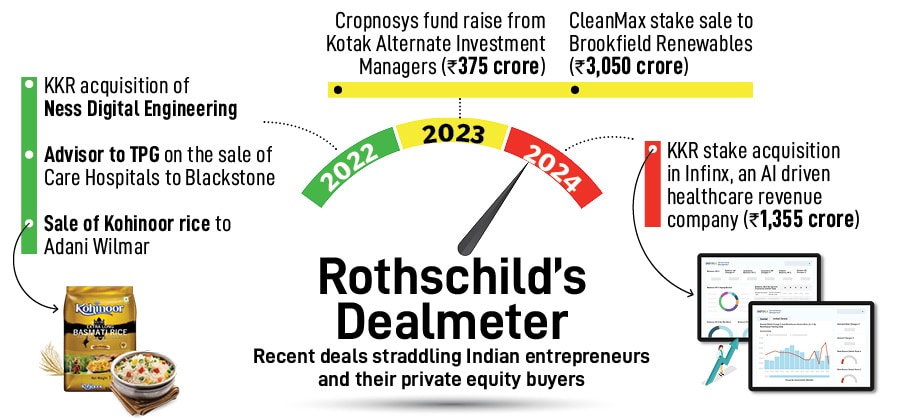

Kotak Strategic Situations Fund invested Rs375 crore (or 55 percent of its FY23 revenue) in December 2023 making this the largest deal in the agri chemical space. And it further cemented Rothschild’s position as a mid-market (defined as transaction sizes of between $100-500 million) deal maker.

Its deals like Cropnosys or the CleanMax fundraise (in 2021 and 2023) that have allowed Indian entrepreneurs and provided Rothschild with an avenue for deal making. They are able to market Indian business to investors both within India and outside—from private equity funds to pension funds and infrastructure funds to sovereign wealth funds.

According to data from Dealogic between 2007-23, Rothschild stood at number three with 151 deals concluded in India, behind Citi and Morgan Stanley that had 165 and 179 deals to their credit respectively.

Its ranking is partly on account of its mid-market positioning in the deals space. That’s where the maximum volume gets generated. “Our view is that we need to be in the flow of things. The more assets we are selling the more value add we can do to the client as we are having many more conversations with industry participants,” Subhakanta Bal, managing director, Rothschild. Globally deal volume is something Rothschild takes seriously. It advised on 379 deals totalling $109.7 billion in 2023.

Changing Face of the Indian Promoter

Rothschild’s 24 years in India provide a ringside view of the changing nature of corporate India. They have seen a greater willingness among promoters to adapt as well as the changing appetite for sectors among deal participants. “There is an openness to ask whether I can take this to the next level or whether it would be better to exit? And if it is better to be an owner or to have someone else manage it,” says Chandresh Ruparel, managing director and head of India at Rothschild. While earlier, it was about being a big fish in a small pond, they are now benchmarking themselves against global peers.

It is this willingness on the part of promoters to look at other options for their businesses has led to a broadening of the M&A market in India. Case in point is deal making in the 2000s that was mainly among corporates, say the Air Deccan fundraise or the Tata Corus deal, both advised by Rothschild, a lot of activity now (both fundraising and disposals) has moved to private equity, which is willing to write the big cheques needed to fuel growth.

Private equity firms are now also more willing to take operational control if things go wrong as compared to the first round of M&A between 2005-12 when they were chasing few investable opportunities and bidding up valuations.

Often the speed of growth catches entrepreneurs by surprise leading to more business for investment bankers. CleanMax, a renewable energy company had done one round of fund raising in 2021 giving Warburg Pincus an exit. Soon the company realised it needed more capital as growth had taken off faster than anticipated. “That is why we had to go back in the market in just about a years’ time because so much happened so quickly in that period,” says Aalok Shah, managing director and co-head India, Rothschild. The next deal in 2023 would be the largest in the commercial and industrial renewable space at $360 million (Rs3050 crore).

A larger sized deal meant that Rothschild cast its net wider reading out to private equity funds, infrastructure funds, pension funds and sovereign wealth funds with a teaser sent out to 35 investors. This resulted in 23 non-disclosure agreements signed and five non-binding offers that were received.

Also read: Why the “venture mindset” is not just for tech investors

The deal had many things coming together. A growth sector, an entrepreneur hungry for more capital, a private equity investor with the capital and more importantly the expertise to take the business to the next level, a regulatory framework that is conducive to growth in the renewable energy space and an investment banker who could market the transaction widely.

Kuldeep Jain, who founded CleanMax, puts this down to the fact that the Rothschild team was able to “work closely with various investors and advisors to ensure that issues raised were addressed quickly and effectively.” “We had a few really good options inspite of a tough market environment,” he says. Jain was also not averse to ceding majority control while raising funds.

For CleanMax, whose portfolio had moved to 1.6GW of rooftop, ground solar and wind solar hybrid projects in FY23, it was important to get in a partner that understood the space and could work with it on the next phase of growth to 5GW.

The deal saw Brookfield Renewable acquiring a controlling stake (through both a primary and secondary transaction) in the company and according to Jain giving it enough capital for the next five years. A job well done could mean Rothschild having to wait a little while longer for more business from CleanMax but as India has shown there will be plenty of other pickings for its 1300 bankers across its 60 offices.

Rothschild’s Indian team of 31 bankers are always on the lookout for deals even when the promoters may not have thought of it. “There are also times when internal discussions are around ‘I have been looking at this sector and it makes sense for the company to do a deal’. This is how one would create deals,” explains Naina Lal Kidwai who in her role as non-executive chairperson spends three-four days a month with the team.

For now, it is mostly the old investor favourites—energy, pharma, IT, industrials, financial services and consumer—that remain in focus. Investors gravitate towards them as they’re known for their steady margin profile, good cash flows and the high multiples that they command. Businesses like, say, cement or real estate could see opportunistic deal making but it is not something bankers focus on.

It is the sectors in focus that often trade at valuations that are over the global average and bankers have their task cut out to get the valuations promoters think they deserve. A part of the reason for this is that in addition to the size of the growth potential of the market it becomes very hard to estimate where the terminal value of these businesses are. For instance, when consumer valuations started rising post Lehman investors argued that these businesses would have to be valued at terminal value after say 20 years. But now, nearly two decades post the Lehman collapse it is apparent that consumer businesses in India are nowhere close to terminal value.

As a result of this global companies at times have to use independent valuations while doing deals on their Indian subsidiaries. In 2023 when Bupa took its stake to 63 percent in Indian subsidiary Niva Bupa they had Rothschild work on the valuation. “While we have our own modelling that we do it is good to have an independent model built in as well,” says David Fletcher, group chief risk officer at Bupa.

In addition to dealmaking and fund raising Rothschild has also been a beneficiary of India’s red hot market for IPOs. Preparing companies for IPOs is a long drawn out process that involves multiple stakeholders. “We prepare a company to list. We work with them on explaining the equity story to investors. What should the business be valued at, the listing price, the bankers to appoint, how to explain the story to the analyst community and what the investor roster should look like,” says Ruparel, explaining their role.

In 2018, Rothschild worked with CreditAccess Grameen on its IPO. At that point, the microfinance sector had seen significant challenges with issues in Andhra Pradesh as well as the business failures like SKS Microfinance.

CreditAccess managed to list successfully in 2018 even though the financial sector was facing headwinds due to the IL&FS crisis. Its portfolio fared well during the Covid downturn but has more recently, along with other microfinance companies, been hit with rising customer leverage and defaults in the sector.

Lastly, there is the debt restructuring where Rothschild advised Air India on paring back its debt. This is a practice area that the team expects a pick up in the years to come along with fundraising and M&A that form its bread and butter.