The good, the bad, and the boogiemen of shoe construction.

A lot of guys start wondering about shoe construction once they’ve moved past their first round of disposable dress shoes. You know the ones—look decent enough out of the box, but after six months the sole peels or the leather creases like paper. That question comes up: What makes some shoes hold up for years, while others seem to age overnight? And is it directly related to price?

The answer, most often, comes down to how the sole is attached to the upper. That connection—its method and its materials—has more to do with longevity than branding or even leather quality.

Importantly though, each construction method, even those considered the most or least durable, has its pros and cons. What activity the footwear is intended to be used for is truly what determines whether the construction used was based on durability or cost-cutting.

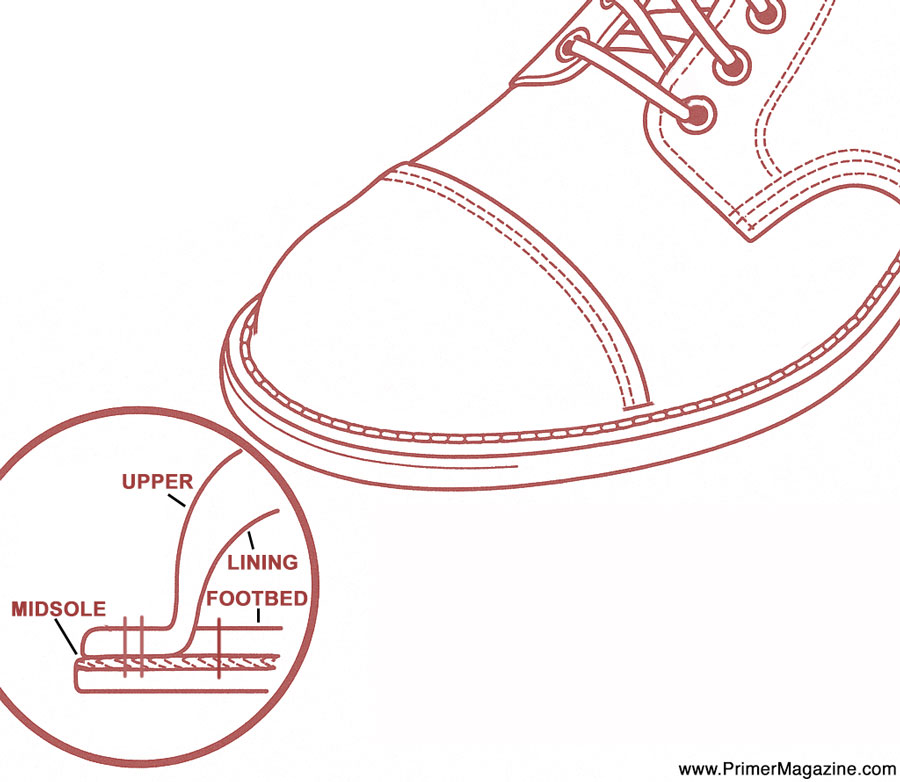

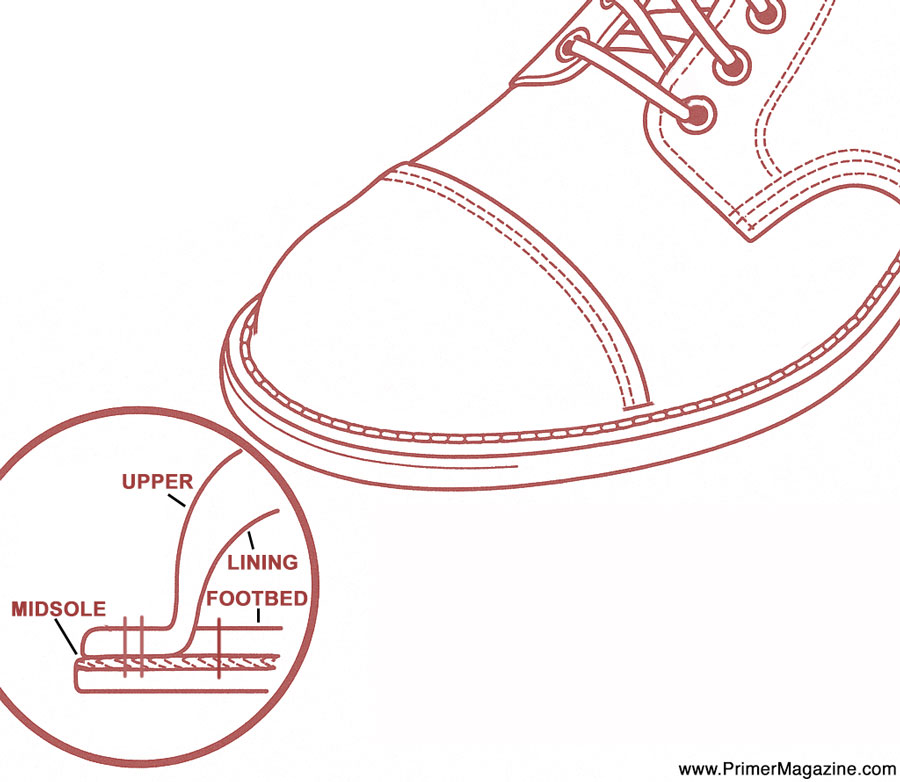

Before we get into the construction methods, we need to start with a quick Primer on

Basic Shoe Anatomy

The Upper

This is the material above the sole that covers the foot—typically leather or canvas. It includes components like the vamp, heel, eyelets, and more.

The Insole

The surface inside the shoe that your foot rests on. It can be cushioned, contoured, or leather-lined, depending on the design.

The Outsole

The bottom of the shoe that touches the ground. Outsoles can be made of leather, rubber, or a synthetic blend.

The Welt

A strip of leather or other material that sits between the upper and outsole on higher-quality shoes. It plays a key role in the durability and resoling potential.

The Last

A 3D model of a foot used during construction. The shape and structure of the last determine how the final shoe fits and looks. Within a brand, different shoe lines may use different lasts which result in different fits, and may be mentioned in the product description.

The different shoe construction methods are not simply “good” or “bad,” or a reflection of quality. Understanding which method can best be used for what kind of shoe will help you make stronger shopping decisions. Knowing how to spend on shoes will keep you from spending more on shoes.

Cold Cement Construction

Invented: Mid-20th century (mass adoption post-WWII), expanded with synthetic adhesives

Cold cementing is the standard method for attaching outsoles in most of today’s athletic and fashion sneakers. It uses strong synthetic adhesives to bond the upper or midsole unit to the rubber or foam outsole—no heat required.

After the shoe’s upper is assembled (often with Strobel stitching, below, or other internal methods), the sole unit is glued on using high-strength cement. The bond sets without heat, allowing brands to use modern foams like EVA, Phylon, or polyurethane that would melt or deform under heat.

What works: Running shoes, trainers, streetwear sneakers, dress sneakers, foam-cushioned casual shoes. Cold cementing enables lighter materials and complex sole designs with air units, flex grooves, or molded shapes.

What doesn’t: Cold cemented shoes aren’t built to be resoled. Once the adhesive bond or foam cushioning wears out, the shoe is effectively at the end of its life. Durability varies by use, but repair options are limited.

Factors like the type of glue, how well the materials are prepped, and how much pressure and time are used during pressing all influence durability. Skipping steps or using cheaper materials can lead to soles separating early.

Cold cementing varies in quality, and unfortunately, it’s not always easy to spot the difference just by looking but there are a few clues. Better cold cemented shoes, like those from reputable athletic or lifestyle brands, use stronger adhesives, prep materials properly, and often incorporate design features like cup soles that wrap the upper for a more secure bond.

The method itself isn’t inherently weak, but the execution makes all the difference.

It’s generally safe to say that if a product page doesn’t mention the construction method, it’s probably cemented—especially for shoes under $200.

Most brands highlight Goodyear welted or Blake stitched construction (both below) as a selling point because it adds value, longevity, and resole-ability. Cemented construction is cheaper and faster to produce, and brands using it often focus marketing on style, comfort, or materials rather than how the sole is attached.

There are exceptions—some small or heritage-inspired brands might not list it clearly, or a Blake-stitched shoe could fly under the radar—but in mainstream retail, no mention usually means cemented.

How to spot it: There’s usually no stitching (or if there is, its decorative and molded into the rubber) around the outsole, just a smooth glue bond where the sole meets the upper. Gently flexing the shoe may reveal separation or a visible glue line on cheaper pairs.

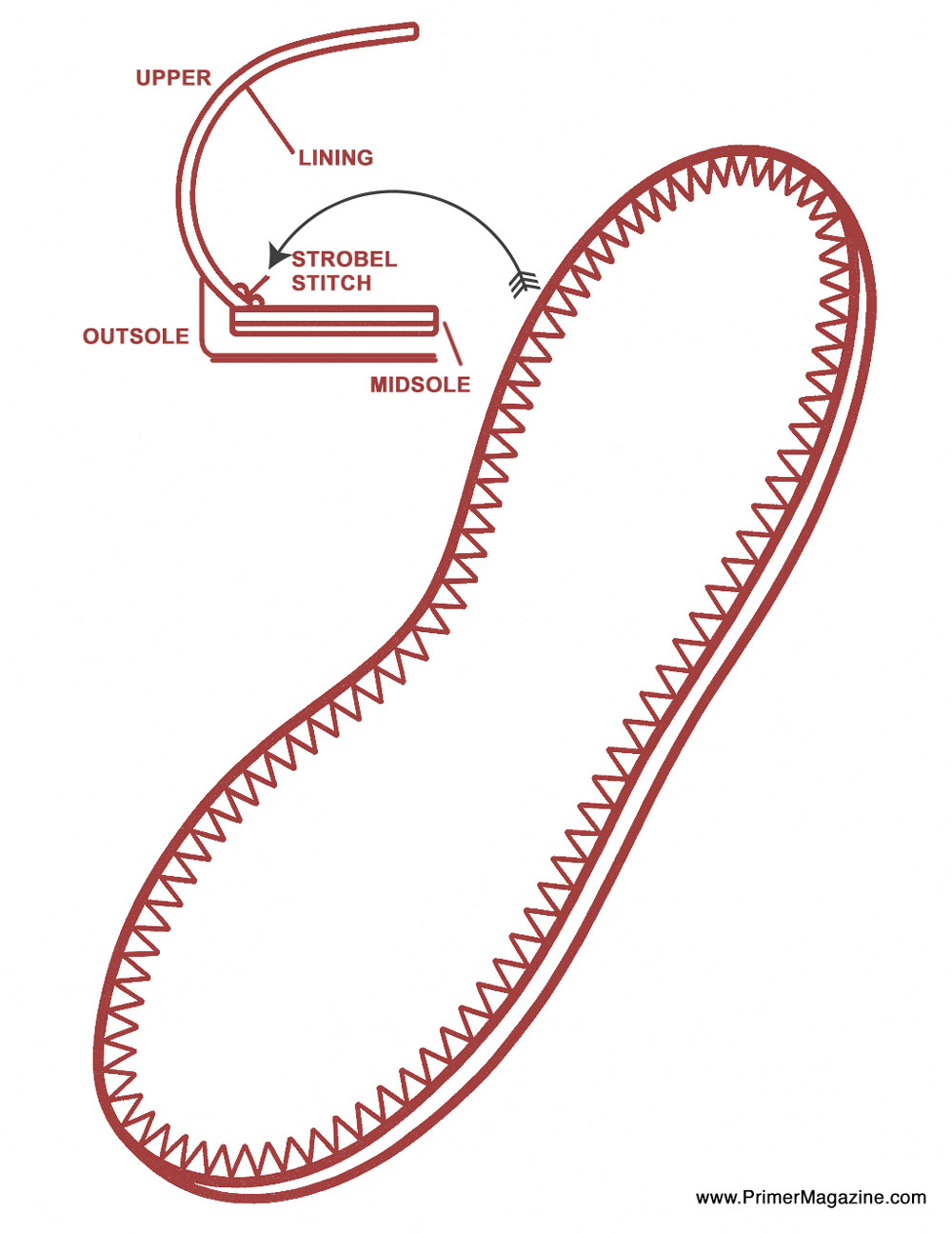

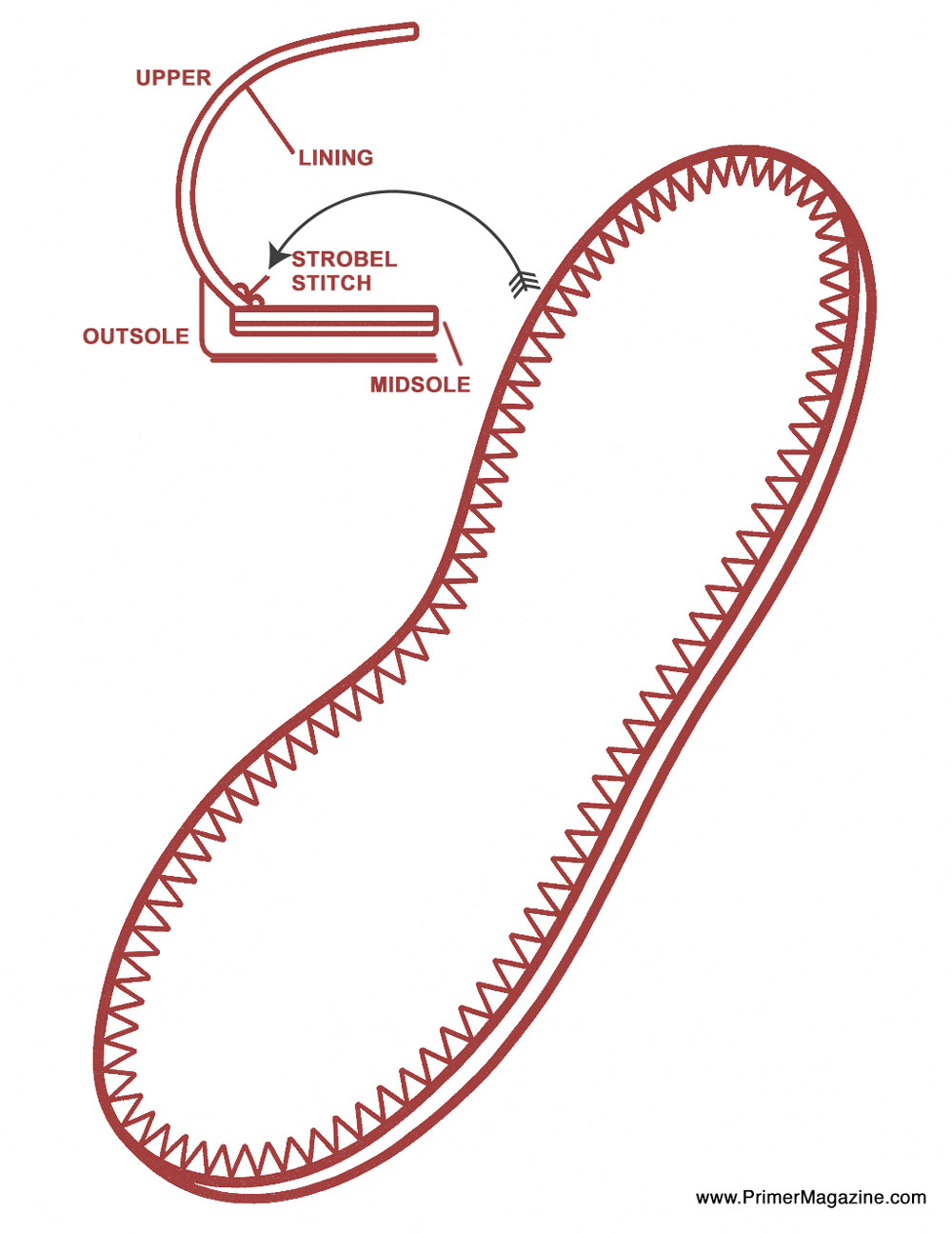

Strobel Construction

Invented: Mid-1900s, named after the Strobel Machine Co. in Germany

Strobel construction refers to how the upper is attached to the insole unit before the sole is applied. In this method, a fabric insole board is stitched directly to the edge of the upper, forming a flexible, sock-like base. This stitched upper unit is then typically cold cemented to the outsole.

Strobel is often invisible to the buyer—it’s what’s under the foot, not under the shoe. But it’s a major reason why performance sneakers feel soft and pliable compared to leather dress shoes.

What works: Ideal for shoes where flexibility, light weight, and a broken-in feel are essential. Think of Nike’s Free or Flyknit lines, or most modern running shoes. The construction allows for natural foot movement and breathability.

What doesn’t: Strobel-built shoes are hard to repair. There’s no welt or structural foundation for resoling. Just like cold cement construction, once the sole wears out or the cushioning flattens, the shoes have to be replaced.

How to spot it: You can’t see it from the outside, but if you lift the insole, you might spot zig-zag stitching attaching the upper to a thin fabric layer beneath.

Blake Construction

Invented: 1856 by Lyman Reed Blake, who worked for the Singer Sewing Machine Company.

Streamlined and sleek, the upper is wrapped under the insole and directly stitched to the outsole with a single stitch running through all layers from the inside. It’s a product of the Industrial Revolution and still common in Italian footwear today.

What works: Slim-profile dress shoes where you want a clean edge and a lightweight, flexible feel. Blake construction also allows for resoling—as long as the cobbler has the right equipment.

What doesn’t: Less water-resistant than Goodyear (below), and the interior stitch can sometimes be felt underfoot. Not every cobbler can work on them, which limits repair options in some areas.

How to spot it: Look inside the shoe, if you feel stitching under the insole but don’t see any along the edge of the sole, it’s likely Blake-constructed.

Vulcanized Construction

Invented: Mid-1800s, based on Charles Goodyear Sr.’s vulcanization process (patented in 1844)

Common in canvas sneakers like Vans and Converse, this process bonds uncured rubber soles to the upper, then bakes the entire shoe in a vulcanizing oven. The heat, around 230°F, hardens the rubber into a durable, springy sole and locks it to the upper without stitching or glue.

What works: It’s ideal for casual shoes made with heat-resistant materials like canvas, suede, or leather. The result is flexible, grippy, and perfect for skateboarding or streetwear.

What doesn’t: Vulcanization limits material choices. Anything that can melt like nylon or EVA can’t be used. It also requires a specialized factory setup, so production is often more niche. You won’t find this method used in high-end dress shoes, and it’s not designed for resoling.

How to spot it: The rubber sidewall wraps up over the upper without any stitching, and the whole shoe feels springy with a slightly rubbery smell, again, think Vans or Converse.

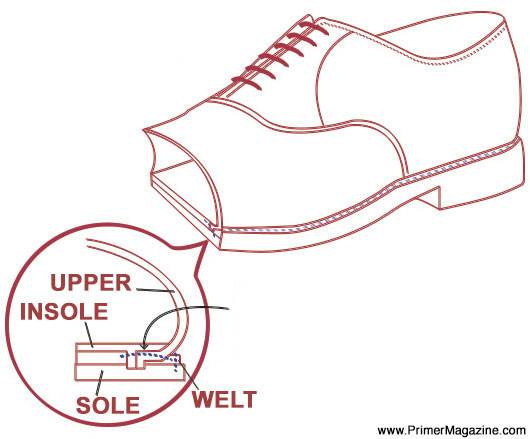

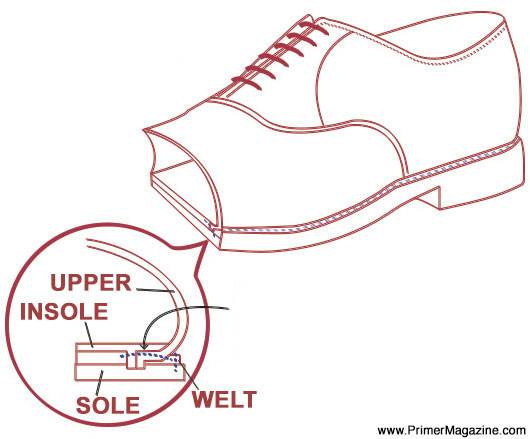

Goodyear Welt Construction

Invented: Patented in 1869 by Charles Goodyear Jr. (son of the rubber vulcanization guy)

The classic standard for durable, repairable footwear. The upper and insole are sewn to a leather welt: a strip that runs around the edge. A second stitch then attaches the welt to the outsole. Between those layers? A bed of cork that molds to your foot over time.

What works: Dress boots, oxfords, brogues, or anything you want to wear for a decade. Goodyear shoes are built to be resoled again and again.

What doesn’t: The extra structure adds weight and rigidity. Takes time to break in before comfortable. Usually more expensive, but for good reason.

Some brands also use a hybrid called Blake Rapid, where the upper is Blake stitched to a midsole, which is then stitched to the outsole—offering more durability while keeping a slim profile.

How to spot it: Look for visible stitching around the outsole’s edge and a small ridge where the welt slightly extends. These shoes tend to feel structured and weighty.

Stitchdown Construction

Origin: Traditional bootmaking, with strong roots in American workwear and Pacific Northwest heritage brands

The upper is flared outward and stitched directly to the midsole or outsole—no welt is used. This creates a broad, visibly stitched perimeter where the upper folds out and becomes part of the sole structure.

What works: A go-to for rugged, water-resistant boots. Brands like Viberg, White’s, Nick’s, and Danner have made stitchdown synonymous with durability. It also appears in lower-cost models like Clarks Desert Boots and some Red Wing offerings, though quality varies.

What doesn’t: Resoling can be tricky. If a cobbler doesn’t carefully reuse the original stitch holes, it can damage the flared leather and compromise the upper. Not every shop is equipped to do it cleanly. Usually you have to ship them back to the brand to be worked on.

How to spot it: Look for the upper leather visibly folded outward and stitched flat against the edge of the sole—there’s no welt, just raw leather and thick stitching around the base. The profile is wide, and the aesthetic leans rugged and functional.

Norwegian (Storm Welt) Construction

Origin: Traditional European bootmaking

A heavy-duty variation of Goodyear welting, Norwegian construction uses a visible double stitch that runs through the upper and welt, then into the outsole. It also often features a raised storm welt that curls upward along the perimeter, adding water resistance. The underlying construction is still Goodyear—the storm welt is a specific style of welt used in the process.

What works: Alpine-style boots, winter-ready dress boots, heritage workwear.

What doesn’t: Bulkier profile and higher cost. Often more style-specific than everyday shoes.

How to spot it: You’ll see two rows of stitching and a raised, curved welt round the shoe’s edge, giving it a chunkier, more rugged profile.

.png?tr=w-1200%2Cfo-auto&w=150&resize=150,150&ssl=1)