One of the key figures in Hong Kong cinema, Tsui Hark is a writer, actor, producer, and groundbreaking director. Born in Vietnam, he attended college in the US before working in Hong Kong television.

Hark directed his first features in the early 1980s. In 1984 he formed Film Workshop, a studio that helped boost the careers of John Woo, Chow Yun-fat, and Jet Li. Shanghai Blues, the first Film Workshop release, brought a revolutionary style and originality to Hong Kong filmmaking. Hark’s other films include the Once Upon a Time in China and Detective Dee franchises, Peking Opera Blues, and entry into the anthology film Septet.

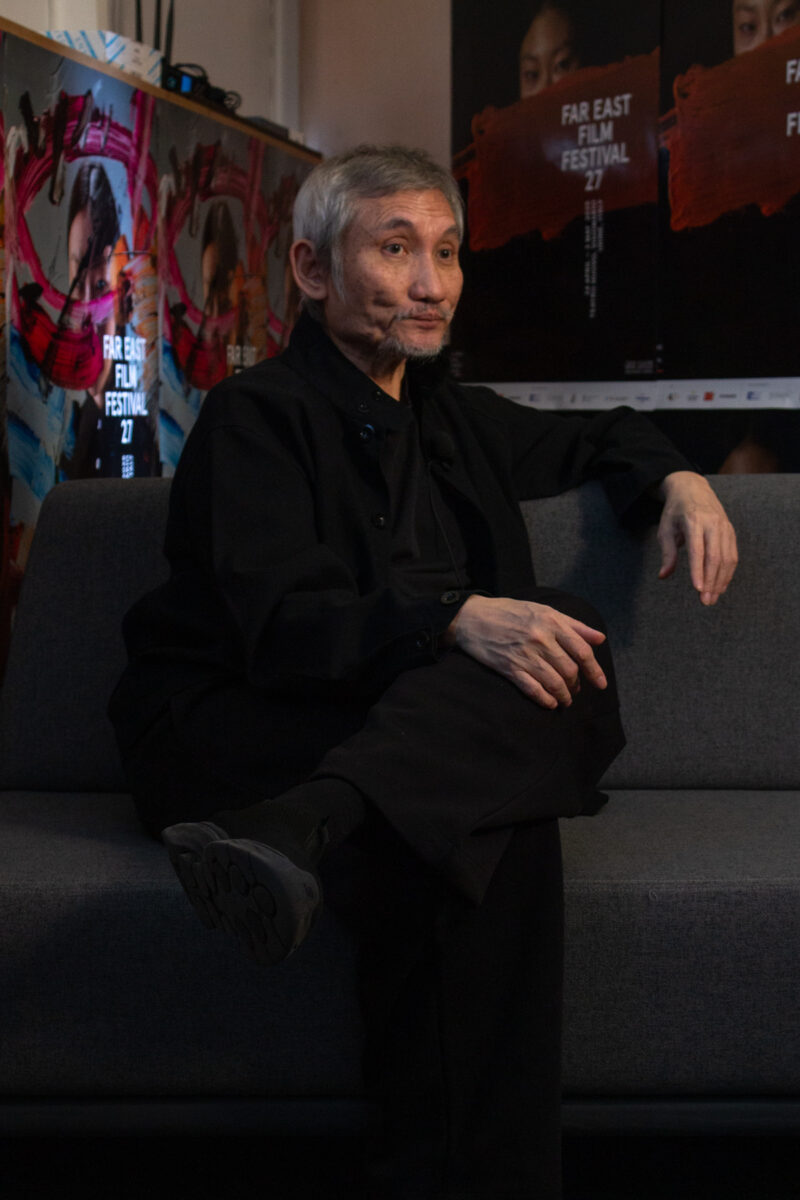

I had the opportunity chat with the legendary filmmaker at this year’s Far East Film Festival in Udine, Italy, where he received the Golden Mulberry Award for Lifetime Achievement, in addition to introducing restored versions of Shanghai Blues and Green Snake, Hark brought his latest film, Legend of the Condors: The Gallants.

The Film Stage: You’ve been adapting the works of Louis Cha and Jin Yong throughout your career. How has your attitude towards his novels changed?

Tsui Hark: Actually, I knew him in-person. A long time ago, he wanted me to adapt one of his novels. I was very frightened because I looked up to him as an idol, and I wasn’t sure I could take on this challenge. Then I started thinking, “If I get this opportunity, how would I do it?” The first of his novels I read was the second part of the Condor Heroes trilogy [The Return of the Condor Heroes]. I was really mesmerized by the romance in his story and was looking forward to adapting it.

But when I worked on The Swordsman [based on Cha’s The Smiling, Proud Warrior] I modified a lot of the plot details. He was not very happy. When I asked if I could adapt his first novel [The Book and the Sword, 1955-56], he said he didn’t have the rights, or something like that. It was a very subtle rejection. He actually turned me down many times after that. A writer like Louis Cha is rarely satisfied by directors who change his work.

By the time I got the opportunity to make Legend of the Condor Heroes: The Gallants, his novels had been adapted so many times that my first concern was not to repeat them. I came up with my own version of the story––my own interpretation of the characters and plot––but in a sincere way to show my appreciation for his work. What I tried to do was return to my childhood, revisit how I felt about the characters in the story then.

What I love about this film is the romantic triangle at the center of the plot. Guo Jing (Xiao Zhang), the hero, is in love with his childhood sweetheart Huang Rong (Zhuang Dafei), a martial arts expert. Hua Zheng (Zhang Whenxin), daughter of the Mongolian emperor, is in love with Guo Jing. All three misunderstand each other. It’s a way of humanizing an epic story, grounding it emotionally for viewers. I feel like it’s a tactic you’ve used throughout your career, like in Peking Opera Blues and Shanghai Blues.

In most movies, if there’s more than one female character, we tend to make one more important than the other. I think it’s interesting to elevate them to the extent that they also can also become friends with each other. That’s what makes the characters in Louis Cha’s stories so wonderful: it’s like you encounter your opposite, and if you’re lucky enough, you become friends.

Udine Far East Film Festival 2025. Photo © 2025 Martina D’urso

Can you talk about the scope of Legends of the Condor?

It’s a very big story. I forget the number of characters, but for 60 years they’ve all been memorable figures for fans of the novel. It was difficult to choose who to include, because people will ask, “What happened to the others?” We focused on the relationship of the three central figures: Guo Jing, the Mongolian Emperor [Baya’ertu], and Venom West [Tony Leung Ka-fai]. Usually, it’s just villain and protagonist fighting and killing each other, but adding the Emperor makes it more complicated. I loved the challenge of making them equally important in the story.

The last part of the novel is about peace. That was very important for me because our world’s in chaos, everybody is fighting everywhere. Countries have their own reasons for war. Peace may not seem very practical or realistic, but my passion is to show viewers that peace is possible.

As for the actual logistics: we had a limited number of soldiers and armor, so we shot the battles in different layers and then composited them. Sometimes the soldiers in the background weren’t totally in focus, which is the sausage part of filmmaking.

Just like Marvel movies. Can we go back to Shanghai Blues, the first film you made with your Film Workshop studio? It’s a romantic comedy with Sylvia Chang, Sally Yeh, and Kenny Bee that stretches from WWII to 1957.

That was 1984, the year I decided to retire. I felt like I’d done the same story so many times that I shouldn’t make films anymore. There were still a couple of stories I overheard or that friends passed around. I offered Shanghai Blues to Yonfan [director of A Certain Romance and other films], but the investors made me switch from producer to director.

I wanted to do something different, but I faced a lot of challenges. There’s no fighting, for example. It’s my first romantic comedy, the first time I could deal with how I viewed women. I don’t know if that’s good or bad, but I tried. Maybe that’s why it’s the most important work in my career. It’s a romance with Sylvia and Sally, but it’s really a story about leaving a place, departing from a city. 1957 was a dark time––no one knew whether to stay or leave for Hong Kong––but we had to make a marketable comedy, which is why we focused on the romantic triangle.

In 1984, it wasn’t very convenient to travel between Hong Kong and Shanghai [the border closed in 1962], so we weren’t very familiar with the locations. We imagined this bridge on the harbor, but it turns out there weren’t any bridges like that.

When you were wrapping up your Once Upon a Time in China series, you directed two films starring Jean-Claude Van Damme: Double Team and Knock Off. How would you describe your experience with Hollywood?

Actually, we didn’t shoot in Hollywood. We shot Double Team in Europe, in Rome. I learned a lot because they were flexible in terms of the people they hired. They came from around the world, which was quite different from our local industry. The heads of department were trained professionals. Hours were shorter. We could have weekends to ourselves––maybe watch a movie at night, go out on the town.

In Hong Kong and Taiwan, it’s different: Taiwan is improving, but in Hong Kong you work like crazy. You never see the sun or the moon. You’re just totally in the film-production world. You never see real people, just your cast and crew. We shot Knock Off in Hong Kong because that’s where the financing was. I thought it might be interesting to bring outside professionals and their systems to Hong Kong to see if we could find some kind of magical combination of filmmaking. Obviously it didn’t work; I was overthinking.

Exactly at that point I decided I would work with our traditional culture, with social situations that were familiar to me. Also respecting our view of the world. On the other hand, filmmakers should not be restricted by place; filmmakers belong to the world because they are sharing feelings with people everywhere.

For every one of my projects, I tried to find a source of energy. For example: with Once Upon a Time in China, I was using my childhood, my dream as a child of those characters. I used to dream that if I had the opportunity, I would make that character I idolized as a kid come alive in the present.

How did The Taking of Tiger Mountain come about?

It was derived from a novel written in the 1960s. The story was adapted into a Chinese opera that was filmed in 1970. It’s also been used by painters and turned into a documentary. I was a projectionist in Chinatown in New York City when I was in my early 20s. I saw that black-and-white film so many times, it made me think that maybe there is some other way to tell the story. When some producers from mainland China asked if I would be interested in making a film there, I said, “The Taking of Tiger Mountain.”

What about Septet, a collection of shorts directed by seven of Hong Kong’s “New Wave” directors?

I’m not sure what “New Wave” means. I was talking with Ann Hui and asked her, “Are we supposed to have some theory or philosophy that makes us ‘New Wave’ filmmakers?” Because we didn’t have theories or philosophies. Of course, everybody––every director––has a way of thinking. But back then we were ignorant of everything, especially the market.

Are you worried about the future of film?

Creativity comes from passion. The feelings communicated between people and the world are based on passion, on the way people interpret their beliefs about life. Creativity will always prevail.